La Cimathèque, centre alternatif du film

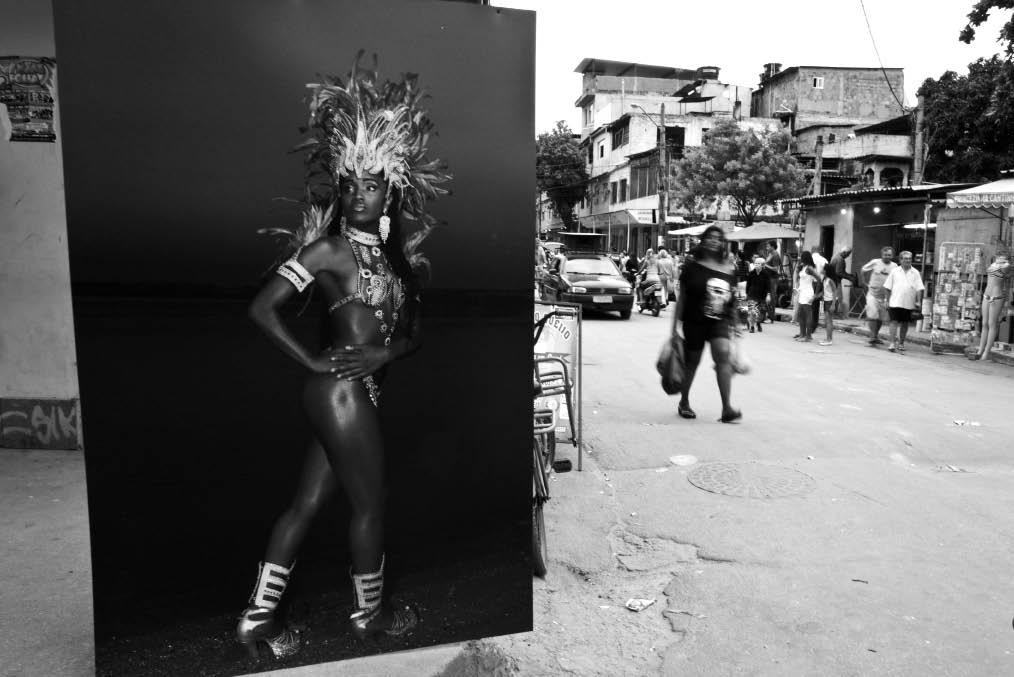

La Cimathèque, un centre alternatif du film, situé dans le centre du Caire a ouvert ses portes le 3 juin 2015. Elle est née d’abord du désir de jeunes cinéastes de créer une société de production indépendante. Avec la révolution le projet s’est étoffé, et la Cimathèque est devenue un lieu de rencontre, de projection, de production, de digitalisation, d’archivage, de débats à l’adresse de tous les cinéphiles. L’Égypte possède une longue tradition cinématographique, interrompue par des années de négligence, de corruption et un manque d’ambition pour un art profondément aimé par la population. La question de l’archivage du patrimoine cinématographique mais aussi des productions contemporaines sur divers supports est centrale dans le projet de la Cimathèque, surtout dans une époque de déconstruction du sens de l’histoire collective.

Cimatheque, Alternative Film Center

Cimatheque – Alternative Film Centre is a multi-purpose venue located in the heart of downtown Cairo. It opened its doors to the public on June 3 2015. It came from the wish of young filmmakers to create an independent production agency. Following the revolution, the scope of the project expanded, bringing about the idea to build an analogue hand-processing lab, the only one of its kind in the country, in the hopes of reviving a lost art form that capitulated in recent years to the cost-effectiveness of digital filmmaking. And because everything that was being implemented in Cimatheque till this point arose from a desire to at once respect legacies and collective histories, while deconstructing their meanings in the current political and social climate, the idea of devoting a room or two to film archives came into being. This concern is central to the way in which Cimatheque’s team approaches programming based on film history and archiving, with the hope that it can give voice and expression to peripheral memories, and material made on the margins of society.